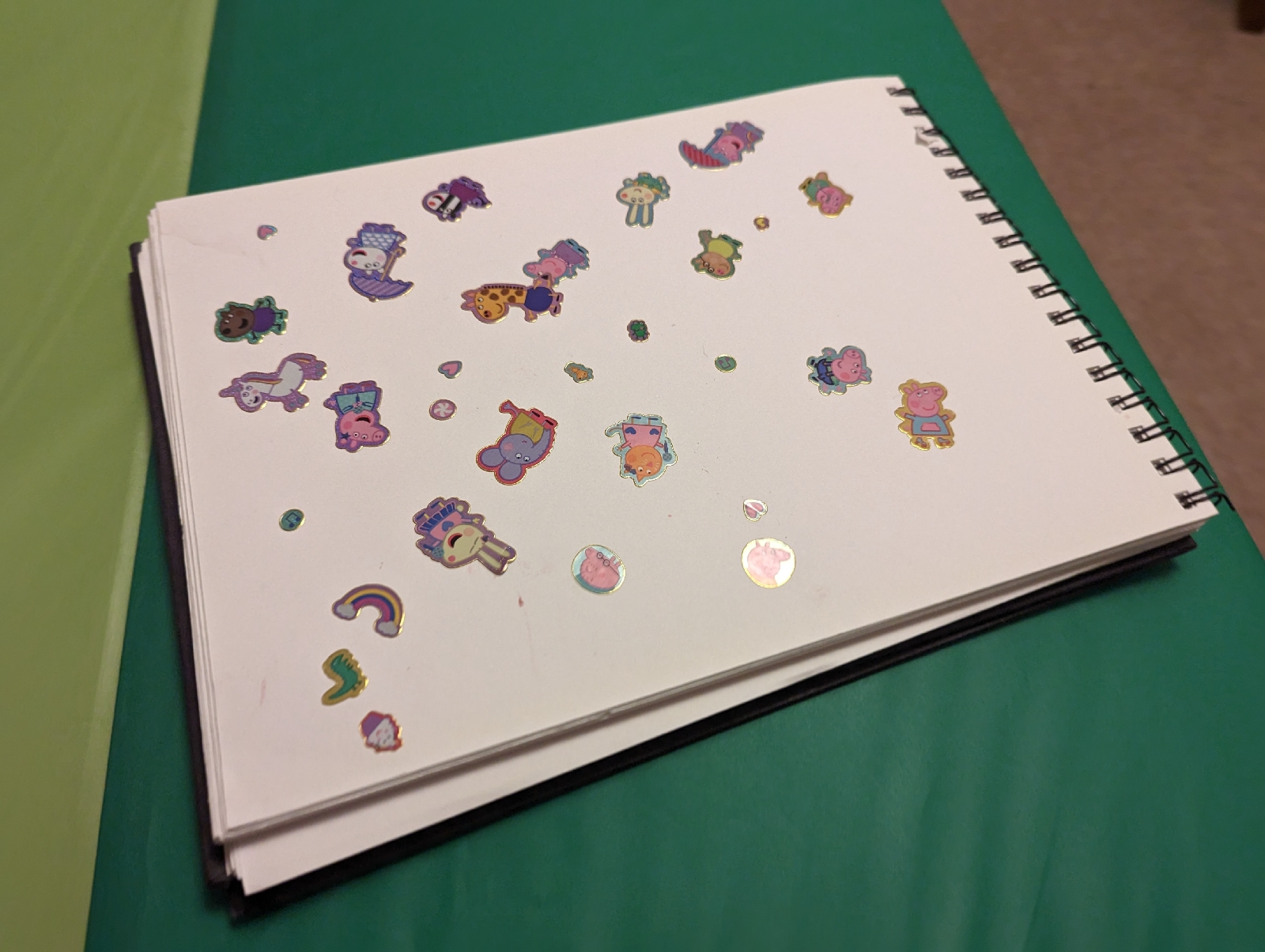

A few weekends ago, my daughter was feeling a bit unwell. On the Saturday morning, we took her to see some highland cows on a nature reserve. She wasn't too interested and seemed a bit lethargic. Before dinner, I sat down with her and some Peppa Pig stickers I'd got the day before. We spent a good 10 minutes peeling them off and sticking them into a sketchbook. We talked about the characters, especially "Mummy Pig" and "Daddy Pig," and she used a word I hadn't heard her use before: "brella," while pointing to Peppa's umbrella. She got some of the smaller stickers caught on her thumbs and asked for help getting them off. "They're really sticky," I said. She lit up at this interaction between us, and her enjoyment of the stickers continued over the next few days.

In the settings I've worked in as an Early Years teacher, a certain pedagogy has mostly held sway. Open-ended and well-built toys, often made from wood, have been the preferred type of resource. There is good reason for this. Wooden toys last longer and are less prone to breaking than plastic. When you have 40 or more children in your preschool class, this is a really important requirement of any toy. Toys that don't automatically signal to children that they have one single use allow those children to use them in any way their imagination chooses, without limiting play to repeating sequences from a TV show. But in settings such as those I've worked in, those adult preferences also come with a little bit of snobbishness around more commercial toys.

I think adults working in Early Years often have their own aesthetic assumptions about what is a 'high quality' resource for children, and what isn't. Yes, children deserve quality, but that doesn't always need to mean Community Playthings blocks or felted small world dolls. To me, a high quality resource is anything that helps to initiate and sustain an interaction between a child and either another child or an adult. I want the resources I make available to my child to stimulate her desire to talk and to excite her. We have lots of wooden toys at home, but I don't automatically see these as better at doing this than a plastic toy or a sticker like our Peppa Pig ones.

I do think practitioners and settings have a responsibility to teach children about and to model sustainability, and to push back a bit against the relentless commercialism that children and families are exposed to. Watching Peppa Pig on TV one morning over Christmas, I noticed how many adverts there were for toys costing "around £30-£100." Parents and carers have enough financial pressures on them already, without their child asking why they can't have the latest Paw Patrol set that they played with at nursery. But wooden toys also come with expensive price tags, partly driven by the perception that they are higher quality, better for child development, and often ethically made. I think it's important to note that many companies producing these toys are using the same marketing tricks to sell their products as big firms like Disney or Moonbug.

What this can lead to is an adult-centred idea of what childhood should look like. Families and settings inevitably make decisions about what type of toys they want their children to play with, and sometimes those decisions are influenced by adult perceptions and emotions about quality, and what kinds of things they do and don't want their child exposed to. To a certain extent, this is fine, but I think it's worth stepping back and de-centering the adult in making these decisions. What do our children like? What are they interested in? For me, it's worth asking those questions and providing at least some toys and resources that show children we care about their answers.

I tweeted about this at the time, and I was quite surprised to find that many of my fellow Early Years practitioners on Twitter agreed with me. There was almost universal agreement that the value of any toy is in its ability to encourage dialogue and to excite interest in the child. Lots of replies suggested rescuing plastic toys from charity shops, or using familiar characters like Peppa Pig to draw children in to play, allowing adults to build relationships of trust and respect with children who may not have been in a setting before. One thought I had, prompted by this conversation, was that the toys we choose to make available in our settings convey a message to our children and their families. It tells them what we respect as culture, and whether we judge families for having plastic toys at home. To me, this is one of the most important tools we have to build relationships with families. We can do this by letting them know that we value their home lives and that we're not here to judge.

I think the best approach is to have a mix of toys. Open ended wooden blocks and loose parts, but also some toys that children will recognise from outside the setting, whether that's Peppa Pig, Iron Man, PJ Masks, or Elsa from Frozen. Giving children the opportunity to combine these two types of resources together might allow for creative and imaginative play beyond what we can conceive of as adults.

Comments

Post a Comment